A Bayesian reworking of a linearized version of L&K, a local method. As outlined in F&W, the gradient constancy assumption can be worked into a matrix formula, where is the predicted velocity at a point:

if . (The are partial derivatives of the video with respect to .)

This doesn’t provide a certainty measure, however. By imposing Gaussian priors on , the noise on , and the noise on , we can obtain an uncertainty measure which primarily depends on the magnitudes of , , and :

where are defined in Outline of the approach and .

However, I think there are some suspicious parts in the math that I don’t really like. Additionally, since this is a local method and basically only involves direct calculation from the image (no iteration or anything), the uncertainty measures given by this method aren’t really tuned and don’t seem super ideal. I’m looking for a probabilistic formulation that allows an explicit (by the model) estimate of certainty for each point in the optical flow.

Tags

Local methods Multi-scale pyramids, coarse-to-fine NOT deep learning Old school Optical flow Probabilistic flow Repeated warping Unsupervised Upscaling flow

Outline of the approach

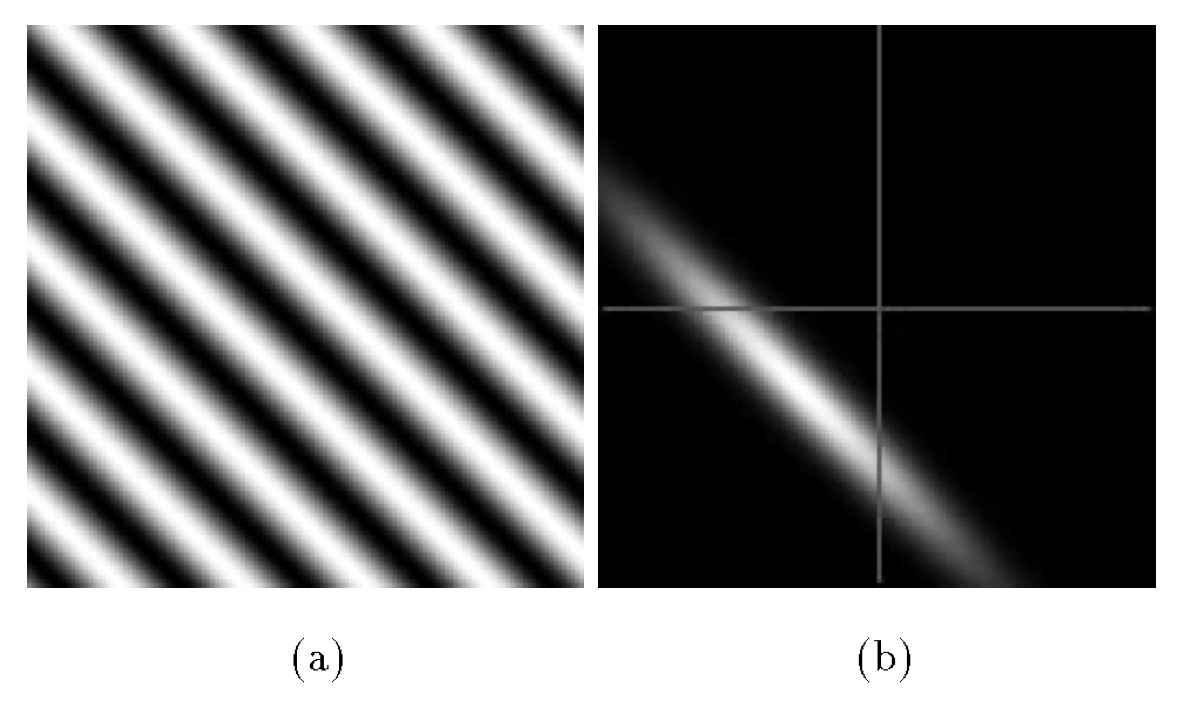

If we just take a single condition imposed by a single pixel, the linearized brightness constancy condition gives us

Now, in reality we might actually have some noise. Suppose that actually has a noise , and that actually has a noise , so the above is not true; instead, we would have

in which we assume that for . I don’t know why is assumed to be noiseless; it seems perfectly natural to have spatial noise. I guess maybe I’ll figure that later on.

Since we have the gradients and want to obtain , we want to figure out what the distribution is. In order to do this, we use Bayes’ rule:

Then gets simplified to , which doesn’t really make much sense to me (is this not just straight up wrong, and clearly depends on ?). The denominator gets reduced to , which is fair as they’re independent.

We then need a prior for , which the authors select to be Gaussian with covariance . Of course this is a reminder that now we are biasing towards .

Finally, with this, they do some math and get the following:

I think this can probably just be directly calculated so I’m not really going to bother checking this. The diagonal form is given above in the introductory section, where and . In that form, the bias is more clearly seen, and I’m not sure if I particularly like it.

Cited

- 1981.H&S—Determining Optical Flow (Horn & Schunck, 1981)

- 1981.L&K—An Iterative Image Registration Technique with an Application to Stereo Vision (Lucas & Kanade, 1981)

Cited By

Return: index